Above the tropical north Pacific waters, over a thousand miles west and a little north of the Hawaiian Island chain, a laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis) wheels in the wind. She is a large and beautiful bird, almost three feet from beak to tail, but with an especially breathtaking wingspan of over twice that. In the air she is poetry, using a flight technique called dynamic soaring, taking advantage of different wind speeds and directions at different altitudes to get where she needs to go with hardly a wing beat. This bird is pelagic, meaning ocean-going. She has a desalinator on board, and the only thing she needs a coastline for is her annual breeding cycle—but then that’s why she’s out here today. She left a mate and a chick in a nest back on Midway Island nine days ago, and they are waiting for her to return with food. She forages mostly at night, sitting on the surface and snagging anything that comes by. She is not discriminating in what she grabs. She needs anything she can get, and after all, out here, thousands of miles from land, there are only two types of substances on the surface: there is water, and there is food. She eats squid, crustaceans, fish and carrion, digesting them in her stomach into a high-nutrition oil for her chick.

By the time she shows up again at the nest, she has been gone for 17 days and has traveled to points over 1,600 miles distant, but her mate had complete faith that she would return. After all, their courtship period was five years long. That’s what it takes to have this kind of trust.

By the time she shows up again at the nest, she has been gone for 17 days and has traveled to points over 1,600 miles distant, but her mate had complete faith that she would return. After all, their courtship period was five years long. That’s what it takes to have this kind of trust.

Her mate is also a female. This is common among laysan albatrosses, in whom the females can outnumber the males by a third. They are a same-sex couple committed for life, and their lives may be over sixty years long. They successfully raise chicks together, fertilized by unfaithful males from nearby nests.

But when this female opens her beak to regurgitate her precious haul down her kid’s gullet, something happens that is getting increasingly common: Out comes a cascade of bottle caps, picnic forks, cigarette lighters, pull-tabs and unidentifiable multi-colored plastic shards.

The chick gulps them down.

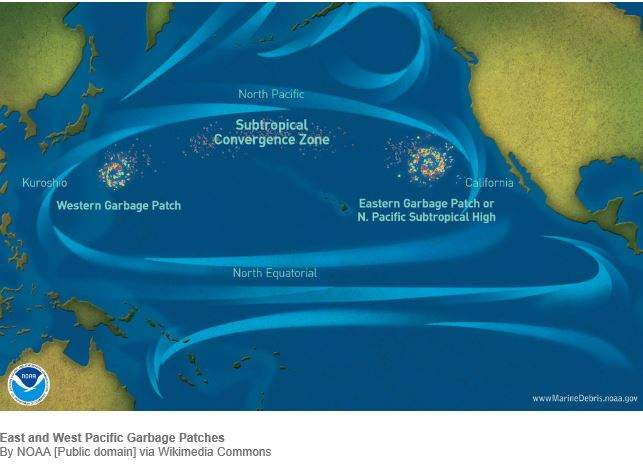

These birds cannot know it, but the waters they forage in are in the middle of a slowly rotating gyre of trash that is bigger than the state of Texas. It’s called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

* * * ** * * *

Probably you’ve heard of it. And probably, like me, you’ve had a few misconceptions about it. First of all, it is not a “patch” in the sense of a dense, visible layer of garbage. It doesn’t look like a landfill. Actually, if you’re not paying close attention you can sail a boat through it without noticing it. A racing boat captain (and now conservationist and oceanographer) named Charles Moore was observant enough to notice it in 1997 when returning from Hawaii after the Transpac sailing race.

Probably you’ve heard of it. And probably, like me, you’ve had a few misconceptions about it. First of all, it is not a “patch” in the sense of a dense, visible layer of garbage. It doesn’t look like a landfill. Actually, if you’re not paying close attention you can sail a boat through it without noticing it. A racing boat captain (and now conservationist and oceanographer) named Charles Moore was observant enough to notice it in 1997 when returning from Hawaii after the Transpac sailing race.

Some of the litter is large, like laundry baskets and flip-flops, but most of the items are small, unidentifiable chips and fragments. They are mostly in the top four feet of water, and they’re not obvious, but if you pull a plankton net through the area you get six times more plastic than plankton. The size of the patch is also very open to interpretation. You usually hear it compared to the state of Texas (poor Texas always gets these analogies), but it depends on how you draw the line around it, and it also changes and moves around constantly with the winds and currents. Ocean gyre expert Curtis Ebbesmeyer says that the patches drift and lurch “like a large animal with no leash,” and when one hits an island, it “barfs” its garbage all over the beaches.

A second misconception is that, I’m very sad to tell you, this is not the only garbage patch. It’s not even the only garbage patch in the North Pacific. There’s another one straight across the water from it, off the coast of Japan. There are five in all, slowly rotating in the world’s major ocean gyres.

The size of the patch is not surprising when you consider the sheer volume of the plastics we discard. The L.A. Times estimates that the Los Angeles River alone washes enough plastics out of its mouth each year to fill the Rose Bowl two stories high. There are probably over seven million tons of plastic in these garbage patches. Some has been there for decades and decades. Some has been there since plastic was invented. Plastic does break down, into water and carbon dioxide, given enough exposure to heat and ultra-violet light. It’s just that it doesn’t happen in the ocean, or at least it doesn’t happen much, because the water keeps it cool and algae and encrusting organisms shield it from the UV light. (It also doesn’t happen underground in our landfills.) So all the plastics gradually concentrate in these gyres, from which there are few exits, and the result is that the first plastic litter ever tossed into the ocean is probably still there. One piece of plastic (which was pulled from the stomach of a dead albatross) bore a serial number that identified it as a piece of a WWII seaplane that was shot down in 1944. Ocean current simulators calculate that it spent a decade in the western garbage patch off Japan, then drifted 6,000 miles across the ocean to the eastern garbage patch, where it spent several more decades before getting eaten by an albatross. Twenty tons of plastic washes up every year on the islands of the Midway Atoll, and five tons of it gets fed to laysan albatross chicks by their parents. The Midways are their biggest rookery. Five hundred thousand chicks are born there each year. Two hundred thousand of them don’t reach adulthood.

Plastic is an accumulator of oily, “hydro-phobic” toxins like DDT and PCBs. The concentrations of these carcinogens in a piece of free-floating plastic in the ocean can be a million times that of the background sea water. The plastics are also sponges for “micro-pollutants” like pharmaceuticals, for instance estradiol, which is the chemical used in birth control. Shellfish like mussels have been observed actually changing sexes. As the plastic litter breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces, it does not change molecularly—it remains plastic, but it can now enter the food chain through the most efficient and abundant collectors on the planet, which are the filter feeders in the surface waters of the ocean, the zooplankton, which are exactly one level above the very basement of the food pyramid, and from there, these chemicals and pollutants magnify further as they ascend the entire food chain and end up on our seafood menus. When they break down even further to the sub-one-millimeter size, almost the molecular level, they are still plastic molecules, but are now capable of being absorbed directly into a cell, and what that will end up meaning no one really knows.

* * * ** * * *

So I know that I have just depressed you and put you in a state of complete despair about the planet we are leaving to our descendants, but believe it or not, I’m about to give you some good news. And it’s not banal, greenwash good news, either—I’m not going to tell you that carrying your recycling to the curb will solve this problem (it won’t). No, this good news is real. The good news is our children. The good news is that there are kids like Boyan Slat on the planet.

Boyan Slat was a Dutch high school kid returning from a diving vacation off Greece several years ago in 2011, thoroughly disgusted after seeing more plastics than sea life. (His diving partner had been enchanted by all the jellyfish. There were no jellyfish. They were all plastic bags.) No sooner did he get back in school than he was asked to do an extra-curricular science project. Okay, he said. He knew about the garbage gyres. He’d read that they couldn’t be fixed. He’d read that they were bigger than the state of Texas. He’d read that cleaning them up by towing nets behind ships would take approximately 79,000 years. The consensus was in from the grown-ups who had created the problem: It couldn’t be fixed. He launched his science project anyway.

Boyan Slat was a Dutch high school kid returning from a diving vacation off Greece several years ago in 2011, thoroughly disgusted after seeing more plastics than sea life. (His diving partner had been enchanted by all the jellyfish. There were no jellyfish. They were all plastic bags.) No sooner did he get back in school than he was asked to do an extra-curricular science project. Okay, he said. He knew about the garbage gyres. He’d read that they couldn’t be fixed. He’d read that they were bigger than the state of Texas. He’d read that cleaning them up by towing nets behind ships would take approximately 79,000 years. The consensus was in from the grown-ups who had created the problem: It couldn’t be fixed. He launched his science project anyway.

“Human history,” Boyan says (he’s a pretty quotable kid), “is basically a list of things that couldn’t be done, and then were done.” The first thing he realized is that it’s dumb to talk about towing nets around behind ships when you’re sitting in the middle of the most famously gigantic gyre of moving water on the planet. It was obvious to him that the thing to do is to anchor something to the bottom and let the currents do the work. “Why move through the ocean,” he says, “when the ocean can move through you?”

Even the fact that the plastics are sponges for toxins was a problem that he turned on its end. That’s a good thing, he said. Hey, sponges are for clean-up. Remove the plastics from the ocean, and you’ve removed the toxins too.

And he hated that word, “nets.” Nets have a mesh size. Nets catch some things and not others. Nets catch things they shouldn’t. Nets ensnare “by-catch” and kill huge numbers of marine organisms. If the plastic trash floats, which it does, then you should only need a fairly shallow boom, impermeable to everything, to cause the floating trash to accumulate on the surface. Any organism under its own power would go under the booms. Plankton, which by definition is not under its own power, would have to be worked with.

What he ended up with was a passive system that just sits there, a V-shaped system of booms tethered to the ocean floor, and, at the crux of the V, a solar-powered, automated processing station. At the processing station there is a slurry pump, along with a centrifugal device which, he had figured out, would separate plankton from plastic, and then a mesh conveyor belt to carry the plastic into a holding chamber for collection. Because the booms are not being towed around, they could potentially be hundreds of kilometers long—which they would need to be to get the job done. He confirmed that the plastics collected are recyclable, and ran some numbers on that. The plastics from all five gyres could bring in $500 million U.S. dollars. The project stood a good chance of becoming self-sustaining, or even profitable. He ran more numbers. He calculated that a 100-kilometer array of booms could clean up half the Great Pacific Garbage Patch in ten years. He put the idea out on social media. He gave a TEDx talk. That created some buzz—and also a lot of scoffing and criticism—but then it all sort of faded. He put his head back down and refocused on the engineering. He worked with a professor to develop a list of fifty questions that would have to be answered in order to call the idea feasible. Answering them would require money. He didn’t have any of that. He was a kid in his bedroom with an idea.

Then, quite suddenly—it happened on March 26, 2013—he looked at his personal email and had 1,500 messages in it. His phone started ringing off the hook. The next day he had thousands more emails. He had gone viral.

Seizing the moment, he launched an on-line crowdfunding campaign. Fifteen days later he had eighty thousand bucks to work with. Volunteers started flocking to him. He started a foundation called The Ocean Cleanup, and launched his feasibility study.

Boyan is twenty-two now, and The Ocean Cleanup has 2.2 million dollars from crowdfunding plus some corporate sponsors, and over a hundred volunteers and staff. They have printed their 523-page feasibility study (between covers of recycled garbage patch plastic). Last month (June of 2016) they deployed a prototype off the coast of the Netherlands. It’s only 100 meters long. They’re going to learn from it, and use what they learn in a pilot project off the coast of Japan that will be two kilometers long. They hope to deploy the full-sized 100-kilometer system in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by 2020. They still have plenty of critics, people both skeptical of the engineering, and people concerned about the possible environmental consequences. After all, this would be the largest man-made structure ever deployed on the ocean’s surface.

But Boyan understands that developing something new is an iterative process, and the software engineer in me just loves that he already gets that. (It took computer programmers about six decades to figure it out.) Boyan says, “We are testing not to prove ourselves right, but to learn what doesn’t work.” So he’s out there doing stuff—building something, listening to his critics, testing, and building something else. Even if The Ocean Cleanup is the most spectacular kind of failure, I will remain humbled by Boyan Slat.

* * * ** * * *

Susan and I are trying to remove plastics from our lives, or at least from our garbage and recycling. We launched the project after returning from a particularly trashy beach hike somewhere between Akumal and Tulum, here on the Yucatan Peninsula. I have to admit here, with all due humility, that generally in our marriage, I am the writer and Susan is the doer, so it is she who is the driving force behind this, and you wouldn’t believe how daunting it looks at first—I mean, look around you. There is just so much plastic in our lives. In fact, Susan and I probably will not be able to get to one hundred percent. But we probably have already gotten to sixty or so, and in only a handful of weeks, and that’s remarkable, and worth doing all by itself. And we’ve gotten there by making changes that are nothing you would call radical. We’re keeping notes and taking photographs. But I won’t go into it all here, because I’m trying to talk Susan into launching her own blog of the project.

Susan and I are trying to remove plastics from our lives, or at least from our garbage and recycling. We launched the project after returning from a particularly trashy beach hike somewhere between Akumal and Tulum, here on the Yucatan Peninsula. I have to admit here, with all due humility, that generally in our marriage, I am the writer and Susan is the doer, so it is she who is the driving force behind this, and you wouldn’t believe how daunting it looks at first—I mean, look around you. There is just so much plastic in our lives. In fact, Susan and I probably will not be able to get to one hundred percent. But we probably have already gotten to sixty or so, and in only a handful of weeks, and that’s remarkable, and worth doing all by itself. And we’ve gotten there by making changes that are nothing you would call radical. We’re keeping notes and taking photographs. But I won’t go into it all here, because I’m trying to talk Susan into launching her own blog of the project.

We’ll keep you posted.

Sources:

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/aconite/dacosta.html

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/laysan_albatross/id

http://www.techinsider.io/boyan-slats-ocean-cleanup-to-clear-the-pacific-garbage-patch-2015-11

https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/7593-The-true-horror-of-the-damage-inflicted-by-plastic-waste-in-the-oceans

http://www.latimes.com/world/la-me-ocean2aug02-story.html

http://www.mindfully.org/Plastic/Ocean/Moore-Trashed-PacificNov03.htm

http://rsbl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2012/04/26/rsbl.2012.0298

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18029015

Thank you for this most informative article.

I wonder what efforts are underway to reduce the dumping of plastics into the ocean.

Living in the Yucatan what would be the environmentally sound way to dispose of plastic?

Thank you for caring enough to ask that question, Tony! There are recycling programs in the Yucatan. You can ask your neighbors. But the broader answer to your question is that, while recycling is worth doing, it will not solve the plastics problem. There is no pretty way to dispose of plastics. Plastics do not recycle, they “down-cycle.” They can only survive the process about once, so something like a water bottle can become something like a dish drainer, but then that dish drainer goes straight to the landfill—or the ocean. The best thing you can do as an individual is, to the greatest extent possible, don’t use the stuff in the first place. Single-use plastics are obviously the worst, so start there. Buy some Kleen Kanteens and some cloth shopping bags. Buy some BeesWrap and chuck your zip-locks. Use aluminum foil and wax paper instead of plastic wrap. Decline the plastic soda straws when they give them to you at the restaurants. You’ll be surprised how easy it is to at least get the single-use stuff out of your life.