One of the most immediately identifiable features of Maya architecture is the corbel arch.

Corbel arches are not exclusive to the Maya or even to Mesoamerica; they can also be found in regions such as Southeast Asia and the Hellenistic world. But without a doubt, it was the Maya who pushed this architectural form to its limits.

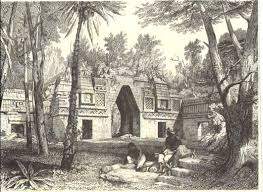

At its core, a corbel arch is formed by stacking stones, with each layer projecting slightly beyond the one below until the two sides meet at the top. While this technique naturally creates a triangular shape, the effect can be masked by using smaller bricks or by incorporating the arch into a larger oval structure.

The Maya used corbel construction for several purposes. They used it to support the heavy stone ceilings of interior temple chambers and passageways, and in the Puuc region of the Yucatán Peninsula, to build suspended stairways  that were easy to walk beneath.

that were easy to walk beneath.

Over time, the corbel arch evolved into a more elaborate structural solution. In some cases, as with the massive arches on the Governor’s Temple of Uxmal, they appear to have been built for purely aesthetic purposes.

During the 19th century, the renowned explorers

During the 19th century, the renowned explorers

The builders behind the arch at Ek Balam, while likely aiming for a similar function, took their plans in an entirely different direction. In this case, while the arch retains its corbel features at its core, it appears more like a temple than an arch. The arch in question is built upon an artificial platform, with access points on all four sides — two of which are scalable through 10 stone steps each, while the other two feature sloped ramps at a similar angle to the stone staircases.

The builders behind the arch at Ek Balam, while likely aiming for a similar function, took their plans in an entirely different direction. In this case, while the arch retains its corbel features at its core, it appears more like a temple than an arch. The arch in question is built upon an artificial platform, with access points on all four sides — two of which are scalable through 10 stone steps each, while the other two feature sloped ramps at a similar angle to the stone staircases. Often, corbel arches also served to separate one part of a city from another. For example, the Serie Inicial (also known as Chichén Viejo) of Chichén Itzá features an impressive arch and ramp that connect to a perimeter wall, effectively cutting this part of the city and limiting access, as it was the only point of access or exit.

Often, corbel arches also served to separate one part of a city from another. For example, the Serie Inicial (also known as Chichén Viejo) of Chichén Itzá features an impressive arch and ramp that connect to a perimeter wall, effectively cutting this part of the city and limiting access, as it was the only point of access or exit. — by

— by

Leave a Reply