Rufino Tamayo left a lasting legacy as one of Mexico’s greatest artists. (Secretaría de Educación Guerrero)

Tamayo’s world was one of color and form before it was a site for ideology. In the decades after the Revolution, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros proclaimed muralism the legitimate voice of the nation — public frescoes that would educate, mobilize and narrate history. Tamayo found this insistence suffocating. He distrusted doctrine and art as a tool of instruction. Yet his rejection was not empty of consequence. Even when he turned away from explicitly political narratives, his choices — palette, subject, shape — carried a quiet politics that helped steer the next generation. He was a pioneer who preferred the interior life of the canvas to the podium.

Making Rufino Tamayo

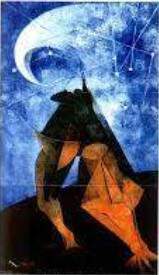

Tamayo’s art fused Mexican influences with the European avant-garde. (Museo Tamayo)

Tamayo’s art fused Mexican influences with the European avant-garde. (Museo Tamayo)

Rufino del Carmen Arellanes Tamayo was born in 1899 in the city of Oaxaca into a modest artisanal household. His father made shoes. His mother sewed. Orphaned young — his father gone, his mother dead — he was sent to Mexico City to live with uncles who sold fruit in La Merced market. The Revolution raged as he arrived, but Tamayo’s  revolution was visual. He fell for the saturated flesh of markets, the watermelon’s deep blush. In the small observations of daily life, he began, without knowing it, to form a theory of color.

revolution was visual. He fell for the saturated flesh of markets, the watermelon’s deep blush. In the small observations of daily life, he began, without knowing it, to form a theory of color.

Pressed by his uncles to study commerce, he chose the only painting school in Mexico City instead: the Academy of San Carlos, where he trained from 1917 to 1920. His first professional post, after the Revolution, was head of Ethnographic Drawing at the National Museum of Archaeology, History and Ethnography. Tamayo later said that

those years taught him more than any school or atelier: how to pare down a line, how to distill a face. He argued — provocatively — that the muted ochres and slate blues that recur in his work were the true colors of Mexico: the colors of poverty. Whether you agree or not, it was his way of seeing the country.

While muralism gathered political energy in the 1920s, Tamayo looked outward. He studied Van Gogh’s brushwork, flirted with Gauguin’s palette and absorbed the European avant-garde. By the late 1920s, he followed many compatriots to New York, the cultural capital for restless artists searching for answers beyond nationalist didacticism. There, in the restless arc of modern art, Tamayo found the means to mix international forms with Mexican matter, braiding modernist structures and Indigenous motifs into a new grammar.

The two world wars had left a tremor in global culture — an anxiety, a collapse of easy meanings — and Tamayo felt it. By the late 1940s, his canvases grew schematic and abstract: figures condensed into planes, color deployed as narrative force. His New York years were formative enough to merit a Smithsonian exhibition decades later. He also

began buying and befriending contemporaries, collecting works that would populate the museum he and his wife would later found.

Olga Flores Rivas entered his life amid paint and music. In 1933, Tamayo was working on the mural “Music and Song” at the National School of Music when Olga, a young piano student, brusquely told him, “I don’t like your painting.” He laughed. Three months later, they married in a church ceremony that surprised acquaintances. Tamayo, the liberal, the iconoclast, in a sanctuary; Olga scandalizing friends in a gray tailored suit with red

trim. She believed, without equivocation, that his gift outshone her own. She abandoned a performing career to become his advocate, the tireless force who opened New York salons and Parisian galleries to his work.

Tamayo, for his part, curated a public myth: the Indigenous Zapotec orphan who had become an artist. The biography was part persona and part strategy, and it worked. Olga’s promotion and Tamayo’s self-making won him solo shows in New York, commissions for public buildings in Mexico, Paris, Puerto Rico and Houston, and a

place at the 1950 Venice Biennale.

The muralists’ doctrine espoused by Rivera, Siqueiros and Orozco had prescribed a single kind of national art: monumental, politicized murals. But Mexico was changing. The nation faced a practical contradiction: land reform and agrarian struggle sat beside industrial projects and a desire to be modern. How to express a Mexico that could honor its past and yet claim a place on the international stage?

An artistic fusion

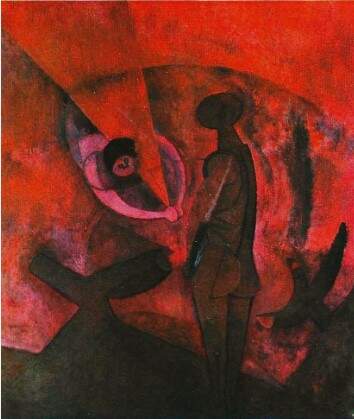

Tamayo proposed an elegant compromise. He borrowed elements of the international avant-garde like expressionist color and cubist simplification, and applied them to Mexican subjects. Color was Tamayo’s language. He argued that bright, saturated hues belonged to the aspirational classes, the palette of what Mexicans desired. The earthy tones — the subdued reds, the heavy blues — that he favored were, to him, the street’s honest hues, the chroma of everyday survival. He painted the dignity of restraint.

A Mexican universalism

As he aged, Tamayo’s argument broadened. He and a cohort of thinkers saw Mexican culture as a hybrid of the ancient and the modern, with the sacred and the technological woven together. For Tamayo, the political act was not a muralized tract. It was the decision to address universal questions — life, death, existence, the cosmos — through

Mexican eyes. Identity, he believed, need not be sloganized. It could be simple and human, a universal creative will expressed through local forms.

Museum and collection

Olga and Rufino amassed a remarkable collection of modern and pre-Hispanic art and founded the Olga and Rufino Tamayo Foundation. From that impulse rose the Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, a compact, discerning institution holding works by Francis Bacon, Jean Dubuffet, Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko and Joan Miró alongside contemporary Mexican artists. The building, by Abraham Zabludovsky and Teodoro González de León, reads like a modern archaeological plinth sitting in Chapultepec, with pre-Hispanic memory refracted through concrete and light.

Olga and Rufino amassed a remarkable collection of modern and pre-Hispanic art and founded the Olga and Rufino Tamayo Foundation. From that impulse rose the Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, a compact, discerning institution holding works by Francis Bacon, Jean Dubuffet, Pablo Picasso, Mark Rothko and Joan Miró alongside contemporary Mexican artists. The building, by Abraham Zabludovsky and Teodoro González de León, reads like a modern archaeological plinth sitting in Chapultepec, with pre-Hispanic memory refracted through concrete and light.

In Oaxaca, they established a companion museum housing Rufino’s deep collection of pre-Hispanic pieces, objects he studied and used as a formal reference until the end. His museums are as much intellectual acts as architectural ones, repositories of the affinities that shaped his eye.

Where to find Tamayo

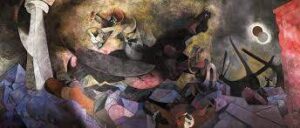

National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City: “Duality” (1964). A mural roughly 12 m. wide, sets Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, against Tezcatlipoca, the jaguar — antagonists whose struggle animates Nahua cosmology. It is one of his great public syntheses.

Tamayo’s “Duality” is exhibited at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. (Wikimedia Commons/Nicolás Boullosa)

Tamayo’s “Duality” is exhibited at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. (Wikimedia Commons/Nicolás Boullosa)

Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City: “Birth of Our Nationality” (1952) and “Mexico of Today” (1953). The first stages the encounter between Europeanized culture and pre-Hispanic worlds; the second celebrates art, science and technique as pillars of modern Mexico.

Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City: houses 38 works and remains indispensable to understanding his range.

Dallas Museum of Art: “The Man” (1953). Commissioned to express ties across the border, Tamayo painted a rooted figure reaching toward the sky — an image of a person seeking a place in the cosmos. That, for Tamayo, was the universal in the Mexican. My personal favorite.

Art Institute of Chicago: fifteen works that chart his stylistic evolution.

New York’s MoMA and The Met: substantial holdings (MoMA nearly 40 works, the Met about 26), though not always on view.

Paris: “Prometheus Bringing Fire to Men” (1958), painted for a UNESCO conference room, remains a striking statement.

Rufino Tamayo’s reputation has sometimes been reduced to a charming shorthand — watermelons and earthen palettes — but that shortcut obscures a richer truth. He loved Mexico with the devotion of someone who reads its streets like scripture: its colors, its crafts, its everyday rituals.

His artistic argument was as much aesthetic as it was civic: Remain connected to the essentials of your culture, and from that rootedness, allow your work to speak to the world.

Leave a Reply