From humble beginnings

As the legend goes, after centuries of subjugation by other peoples of Aztlán, the people who history would know as the Aztecs were commanded by the god Huitzilopochtli to migrate south in search of a new home. Under the leadership of their first ruler, Acamapichtli, they began their journey. Some legends and scholars, as far back as the 16th century, claim that during this migration, great cities like La Quemada in modern Zacatecas were built. Still, we  lack archaeological evidence to back up these claims.

lack archaeological evidence to back up these claims.

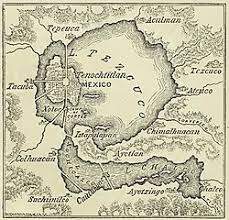

This great migration finally came to an end in Anáhuac, the ancestral home of the Nahuatl (remember not to pronounce the tl), which surrounded the once great Lake Texcoco, and where the largest concentration of settled Nahuatl peoples lived, including the Acolhua, Chalcas, Tepaneca, and Mixtec.

Despised as barbarians, these once nomadic people shed their Aztec identity in favor of the name Mexica, which means those who live in the navel of the moon.  Being newcomers to the region, the Mexica were forced to take refuge on an uninhabited island in Lake Texcoco, where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus — a sign from Huitzilopochtli that this was their promised land. In 1325, they founded Tenochtitlán, a city that would one day rival the greatest in the world.

Being newcomers to the region, the Mexica were forced to take refuge on an uninhabited island in Lake Texcoco, where they saw an eagle perched on a cactus — a sign from Huitzilopochtli that this was their promised land. In 1325, they founded Tenochtitlán, a city that would one day rival the greatest in the world.

A controversial moniker

The term “Aztec” is somewhat of a misnomer. The people we commonly refer to as Aztecs called themselves the Mexica (pronounced meh-SHEE-ka), part of a larger Nahuatl ethnolinguistic group. The name ‘Aztec’ derives from the name of a mythical homeland by the name of Aztlán, which translates as “Place of the Herons”.

The label “Aztec” gained popularity in the 19th century, thanks to European scholars like Alexander von Humboldt and William H. Prescott, who popularized the term in their writings. While some modern historians prefer “Mexica” to emphasize their self-identity, “Aztec” remains entrenched in popular culture, often used to describe not just the Mexica but also their allies in the Triple Alliance (Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan).

The turning point in Aztec history

In 1426, the powerful Tepanec ruler Tezozomoc died, plunging Azcapotzalco into a succession crisis. The Mexica, led by their shrewd tlatoani (king) Itzcoatl, saw an opportunity to fill the political vacuum. Alongside their allies in Texcoco and Tlacopan, they rebelled against the new Tepanec ruler, Maxtla, in a brutal war that reshaped the balance of power in the region.

By 1428, the Mexica and their allies emerged victorious. This victory marked the birth of the Triple Alliance—a military and political pact between Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. Though nominally equal, Tenochtitlán quickly became the dominant force, setting the stage for imperial expansion. But make no mistake: Though Texcoco and Tlacopan were powerful, true power rested with the Mexica.

The Mexica succeeded through a combination of military prowess, strategic alliances, and ideological unity. Initially outcasts, they honed their skills as mercenaries, mastering warfare and forming the elite Eagle and Jaguar warrior orders. They imposed a tributary system that extracted wealth without direct rule, ensuring control over vast territories without overextension. Religiously, their belief in Huitzilopochtli’s demand for constant warfare justified expansion, uniting their society under a divine mandate. Ruthless yet pragmatic, they exploited rivalries among enemies, rewarding loyalty and crushing dissent. This blend of martial discipline, political cunning, economic efficiency, and sacred purpose transformed them from refugees to empire-builders.

A swift and dramatic downfall

The Mexica Empire’s fall came swiftly between 1519 – 1521 when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés exploited political fractures and unleashed biological warfare. After being welcomed into Tenochtitlán as guests, the Spaniards turned on Emperor Moctezuma II, taking him hostage. Though initially expelled during La Noche Triste (June 1520), Cortés returned with thousands of Indigenous allies, particularly the Tlaxcalans and Tarascans, who bitterly fought Aztec domination. The final siege starved the city while smallpox ravaged its defenders. Cuauhtémoc, the last tlatoani, surrendered on August 13, 1521, marking the end of Mexica sovereignty. The Spanish razed Tenochtitlán, building Mexico City atop its ruins, while surviving Mexica nobility were absorbed into the colonial system. Their defeat resulted from technological disparities, epidemic devastation, and most crucially, the rebellion of subjugated peoples against Aztec rule.

The Mexica Empire’s fall came swiftly between 1519 – 1521 when Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés exploited political fractures and unleashed biological warfare. After being welcomed into Tenochtitlán as guests, the Spaniards turned on Emperor Moctezuma II, taking him hostage. Though initially expelled during La Noche Triste (June 1520), Cortés returned with thousands of Indigenous allies, particularly the Tlaxcalans and Tarascans, who bitterly fought Aztec domination. The final siege starved the city while smallpox ravaged its defenders. Cuauhtémoc, the last tlatoani, surrendered on August 13, 1521, marking the end of Mexica sovereignty. The Spanish razed Tenochtitlán, building Mexico City atop its ruins, while surviving Mexica nobility were absorbed into the colonial system. Their defeat resulted from technological disparities, epidemic devastation, and most crucially, the rebellion of subjugated peoples against Aztec rule.

The aftermath

Even if one were to trace the rise of Aztec power to the foundation of Tenochtitlán in 1325, and its fall at the hands of the Spanish in 1521, that is under two centuries. This point is especially poignant when we consider that the vast Aztec empire exercised its might across Mesoamerica in the latter half of these two centuries. In historical terms, that is a flash in the pan.

But the legacy of the Aztecs is hard to exaggerate. For one, the name Mexica lives on in the name of México, and its legendary heraldry still flies proudly on the Mexican flag. But in a sense, the Aztecs have also become a stand-in for the accomplishments of dozens of civilizations, like the Toltecs, Mixtecs, Choltultecas, the builders of the mysterious city of Cuicuilco, and even the Teotihuacans.

The word Aztec brings to mind a vast empire, grand pyramids, bloody wars against other Mesoamerican peoples, and their sudden cataclysmic fall at the point of European iron swords. Yet, the very name ‘Aztec’ is a subject of debate. Who were these people, where did they come from, and why are we still fascinated by Aztec history today?

The word Aztec brings to mind a vast empire, grand pyramids, bloody wars against other Mesoamerican peoples, and their sudden cataclysmic fall at the point of European iron swords. Yet, the very name ‘Aztec’ is a subject of debate. Who were these people, where did they come from, and why are we still fascinated by Aztec history today?

Leave a Reply